- The Scholarly Letter

- Topics

- Essay

EssayEssay

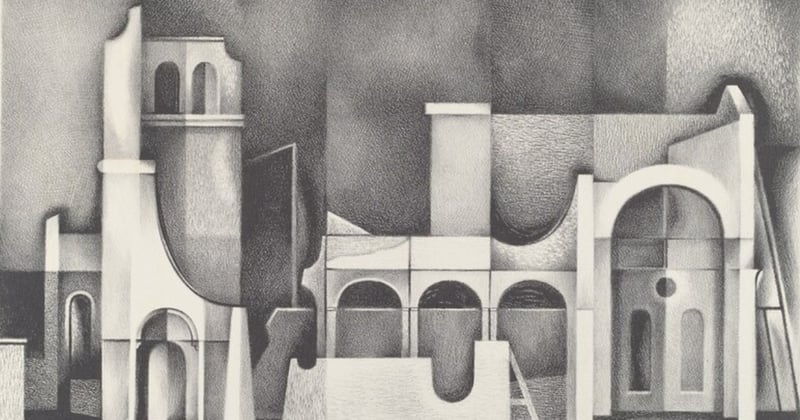

Anti-University: Scholarship Before, Within, and Beyond The University

Private universities now receive government funding, public universities prize industry partnerships, and liberal arts colleges emphasise the development of graduates capable of contributing to a nation's economic prosperity and security.

EssayEssay

EssayEssay

EssayEssay

EssayEssay

EssayEssay

EssayEssay

EssayEssay

EssayEssay

EssayEssay

EssayEssay