- The Scholarly Letter

- Posts

- What if Scholarship Looked Like This?

What if Scholarship Looked Like This?

“A paper that does not have references is like a child without an escort walking in the night in a big city it does not know: isolated, lost, anything may happen to it”

🍎your Scholarly Digest 24th July, 2025

Essentials hand-picked fortnightly for the mindful Scholar

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to receive weekly letters rooted in curiosity, care, and connection.

Know someone who will enjoy The Scholarly Letter? Forward it to them.

All previous editions of The Letter are available on our website.

Hi Scholar,

Over the last few months, something has been igniting inside us. A burning desire to do something for the scholar, and for scholarship.

You may have noticed it in our writing.

The Critic wrote of her decision to step outside the walls of academia while remaining deeply committed to building a commons for scholarship.

The Tatler, in his last essay, outlined a vision for an alternative model of scholar-led knowledge creation.

Together, we’ve written about reviving the figure of the scholar – reclaiming scholarship from the ruins of neoliberal academia, and returning it to care, curiosity, and community.

And so, to move these hopes and dreams out of the text and into the world, we’ve taken the next step:

We’ve officially registered The Scholar Initiative CIC - a not-for-profit organisation established to serve the interests of the scholarly community that has begun to take shape here, in this space.

Written into the fabric of this organisation is a promise to serve scholarship - not private or personal interest.

It’s the beginning of something bigger. A foundation – not for a start-up, business, or an academic centre – for a cultural shift. A way to give form and anchor to what we’ve been building here together.

Right now, we’re just a couple of scholars with a newsletter, a small website, and a handful of ideas. But we’ve begun to recognise: this isn’t just writing for the sake of writing. It’s community. You, reading this, are part of it.

So we’re building an organised para-academic space for scholarship and scholars. For those inside or outside the traditional university who want to dedicate themselves to, and be in a relationship with, knowledge.

The aim of The Scholar Initiative is to help bring about a cultural shift: one that revives the figure of the scholar and their commitment to learning, knowing, and thinking, not just within the institution of academia, but beyond it.

Scholar, we are committed to you.

BRAIN FOOD

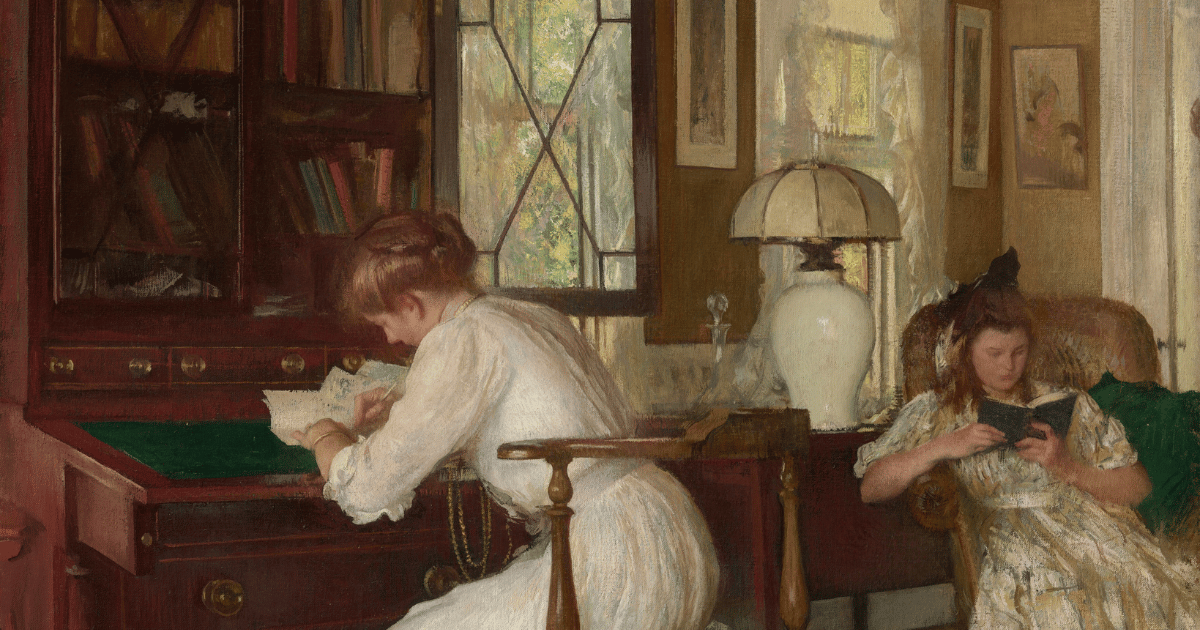

What If Scholarship Looked Like This?

When we think of collaboration in scholarship, we often think about it as a positive force: something that allows us to connect with fellow scholars, engage with each other’s ideas, and create something together that could not have been made alone. But in recent years, this idea of collaboration has been territorialised. It has become yet another tool for boosting productivity in the academic research culture.

Nick Butler and Sverre Spoelstra, in their paper Your Excellency, offer a critique of this phenomenon. They show how collaboration has been instrumentalised, turned into a tactic for publishing more papers through rotating first authorship or paper-swapping strategies that function like a “two for the price of one” deal: two colleagues work on separate papers, each contributing “eighty, eighty-five percent,” and then are listed as authors on both. Collaboration, in this form, becomes not only another mechanism for surviving the publish-or-perish economy of neoliberal academia but also reinforces it.

There is something perverse about this. Collaboration, at its heart, is not about efficiency or increasing output, but about becoming together. It is a way of opening ourselves to others to allow for mutual shaping, reflection, and transformation. It is about what emerges through our relations and connections with one another, not what can be extracted from them.

This is the line of thinking that Khang and his colleagues take up when they ask what it means to collaborate otherwise. In response to their own sense of loss – loss of meaning in their work as sustainability scholars – they turned to collective letter writing. Drawing on Kallis and Swyngedouw’s idea of letters as academic conversation, they embraced letter writing as a practice of thinking-together, imagining otherwise, and reclaiming the joy and care of scholarship as community.

These letters weren’t about saying the right things, sending clear messages, or publishing findings. They were about asking questions, sitting with ambiguity, and opening up space for dynamic reflection. Collective letter writing, in this manner, offers

an affective experience of togetherness not defined by the output.

That, we believe, is what collaboration could mean again.

In this mode, collaboration is reclaimed from the hold of productivity. It becomes less about what to do with the writing – where to submit it, how to format it, how many ‘experienced’ co-authors it needs – and more about what the writing does to us. What kind of thinking it invites, what kind of intimacy it allows, what kind of solidarity it makes possible. After all, wasn’t the whole point of working together, of writing to one another, of creating scholarly work, always to be in conversation?

Collective letter writing, unbothered by publication metrics, may be one of the last remaining forms of scholarly work that resists the demand to produce and instead returns us to the desire to connect. Imagine having an idea and simply writing it out, as if sharing it with a friend. Sending it to them. Maybe they read it aloud to a colleague, maybe they write back, and maybe even others join. The idea grows, not as a citation count, but as a living network of dialogue.

We’ve spoken before about the Republic of Letters, the transnational intellectual community of the late 17th and 18th centuries which existed through a network of letters. That was how scholarship used to travel: not through journals, but through letters. Perhaps a turn to collective letter writing will not only revive that mode of scholarly life, but also work as resistance to the cold regime of academic productivity.

Khang and his colleagues write, and we join them in asking you, Scholar:

Can letter writing be one way of reading/writing/thinking intimately together? What if scholarly writing were more like letter writing? How would that invite a special form of knowing and being in academia?

And we ask further:

Why don’t you write letters, Scholar?

We write to you every week. Why don’t you write back?

Why don’t you share your thoughts, your questions, your reflections – not for prestige, not for publication – but for conversation? Has the regime of scientific writing, of writing only for peer review, constricted your voice to the point where you’ve forgotten how to write freely?

It doesn’t even have to be to us. But we invite you to write – to a colleague, a friend, yourself – to become together, to revive scholarship as a community.

NEWS

Can You Regulate Integrity?

For many years a PhD candidate at an Indian institution was required to have 2 or 3 published peer reviewed articles before they would be allowed to submit their thesis and graduate. Similar requirements - that a PhD candidate has either published or at least submitted articles to journals before they can defend their thesis - have existed at the country-level in China and also at the university-level all around the world at various times. It is easy to understand why these rules were introduced in a system where a publication record is essential for starting what is considered a “successful” academic career. Publish or perish culture is universal in academia, however, the existence of codified requirements in certain countries or institutions pushes it even further. By creating bureaucratically enforceable barriers to career progression for academics, it is no longer a case of a hiring committee's subjective decision but cold, hard numbers.

When faced with codified rules such as these, it is perhaps not surprising that some academics turn to questionable research practices in order to advance their careers. Indeed, enforcing stricter publication requirements may have been detrimental to a country's overall research culture - 8.2% of highly cited authors in China and 9.2% in India have had articles retracted, far higher than in other parts of the world.

Over the last 5 years, India’s research output has grown rapidly with many of its universities also rising in the global rankings. These encouraging signs have however been overshadowed by an accompanying rise in retractions, with Nature identifying Indian institutions as one of several global “retraction hotspots”.

All of the above is a necessary prelude to this week's News: India’s independent body for accrediting and ranking universities - the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) - has announced that universities will now be penalised for retractions.

For the majority of its existence, academia has been capable of self-regulation, ensuring high quality research without oversight from independent regulatory authorities. Whether we like it or not, research integrity has in recent years become an increasingly serious problem for both the credibility and effectiveness of academic research. In this context, the NAAC’s announcement feels not only timely, but necessary.

RESOURCE

Think Harder, Scholar

This week’s resource is a video essay titled Cognitive Hygiene: Why You Need to Make Thinking Hard Again.

We won’t summarise the content of this already short video – just over five minutes – as that may defeat the whole point (and perhaps even the exercise) of watching it. Instead, we’ll leave you with this line from the video, which might just tempt you to spare a few minutes of your time:

Knowledge without contact. Facts without fiction. Intelligence as a service.

A small heads-up: it’s read in a somewhat jarring tone, but the content is solid.

OPPORTUNITIES

Funded PhDs, Postdocs and Academic Job Openings

Postdoctoral Positions @ University of British Columbia, Canada: Postdocs: click here

PhD and Postdoctoral Positions @ University of Antwerp, Netherlands: click here

PhD Positions @ University of Edinburgh, UK: click here

PhD Positions @ University of Copenhagen, UK: click here

KEEPING IT REAL

In Case You Missed the Reference

The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice by Annemarie Mol is a highly unusual book. It is, in effect, two books printed one on top of the other: the top half of the page devoted to what she calls the “upper text” and the bottom half devoted to the “subtext”. A quote from the subtext that begins on page 30 reads:

“In this book I reflexively attend to the genre of “relating to the literature.” I am not all that comfortable with this genre, for there is the danger that it implicitly strengthens a number of assumptions against which the text is making explicit arguments. Besides, it is never possible to relate to the literature specifically enough. Out of sheer love for detail, I would prefer to not include any references at all, since they will inevitably be too crude. But that is not wise. “A paper that does not have references is like a child without an escort walking in the night in a big city it does not know: isolated, lost, anything may happen to it” (Latour 1987, 33). Presenting this quote is a way of relating to the literature that I will use only sparingly throughout this book: treating it as a source of authority.”

This passage eloquently addresses the complicated nature of referencing previous works we all have experienced but perhaps never quite articulated so beautifully. Citing previous works is never as straightforward in practice as it appears. In reality, we may draw on only certain parts of a previous work, yet to inform our reader which parts we support and which we do not is practically impossible. At the same time, we can never truly credit all the sources that have informed our work: no matter how hard we try, the final list of references will be, as Mol puts it, “too crude”. Despite all of these ambiguities, we cannot do away with referencing entirely either.

This column in The Scholarly Letter is the space where we like to put things that speak to the personal, human, nature of scholarship. It is where we can appreciate the lighter side of what it means to engage with knowledge and drop the facade where we all pretend to know what we are doing. The paragraph quoted above is just that.

Which section did you enjoy the most in today's Letter? |

We care about what you think and would love to hear from you. Hit reply or drop a comment and tell us what you like (or don't) about The Scholarly Letter.

Spread the Word

If you know more now than you did before reading today's Letter, we would appreciate you forwarding this to a friend. It'll take you 2 seconds. It took us 27 hours to research and write today's edition.

As always, thanks for reading🍎