- The Scholarly Letter

- Posts

- Anti-University: Scholarship Before, Within, and Beyond The University

Anti-University: Scholarship Before, Within, and Beyond The University

Private universities now receive government funding, public universities prize industry partnerships, and liberal arts colleges emphasise the development of graduates capable of contributing to a nation's economic prosperity and security.

Anti-University: Scholarship Before, Within, and Beyond The University

Your Thursday Essay 5th February 2026

Become a member of Scholar Square, our online digital community where we put our ethos into practice - and get access to all editions of The Scholarly Letter for free.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to receive weekly letters rooted in curiosity and connection.

Know someone who will enjoy The Scholarly Letter? Forward it to them.

All previous editions of The Letter are available on our website.

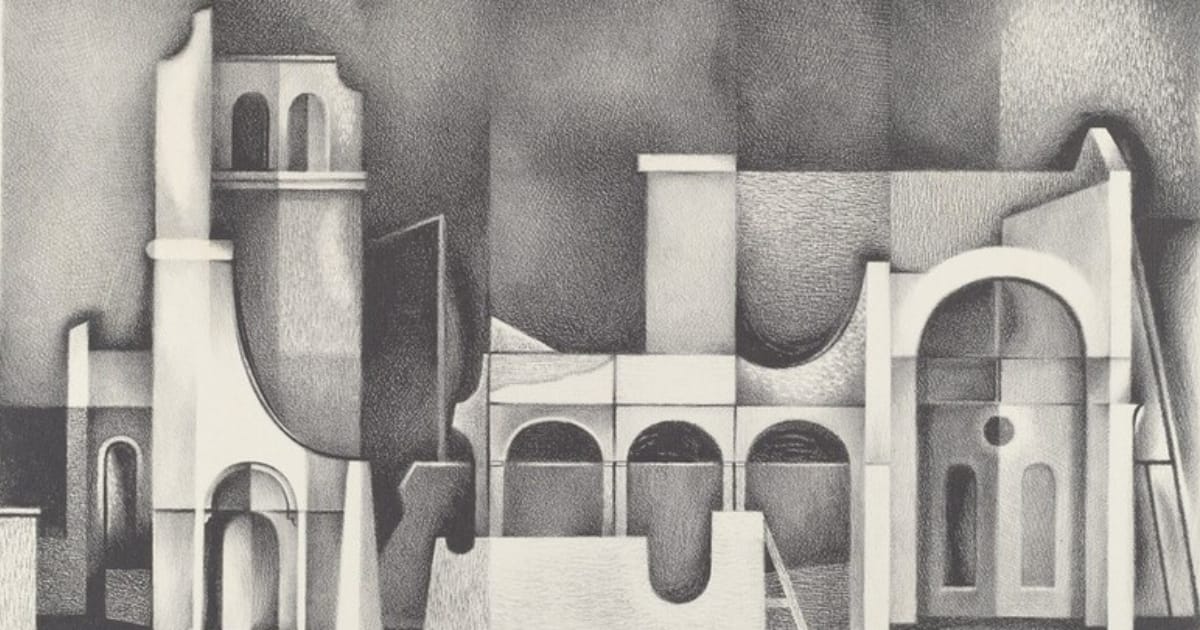

Online Thumbnail Credits: National Gallery of Art

Hi Scholar,

Recently, The Tatler took to social media to announce his decision to pursue an independent PhD by publication:

“The goal I set myself this year is to earn my PhD by January 2032.

I won’t be enrolling in a formal program. I won’t be affiliated with a university. I’m going to do it independently. Being independent means being outside traditional funding, outside traditional institutions and doing a different kind of scholarship than what is common in academia.

I’ll be working towards my PhD by publication. Instead of a monograph/thesis, I will spend the next 6 years working to publish between 3-5 peer reviewed journal articles. When taken together, these publications will form a coherent, original body of work that is equivalent to the contributor of a standard PhD thesis. My topic is broadly in intellectual history/history of science. I’m interested in how shifts in scholarly practices, institutions, and norms in the 20th century have shaped contemporary academia today.

If you believe that a research grant and a lab are needed for you to be a scholar, then traditional academia is where you can find them. But that support comes at a cost. You can’t have it all. It takes some imagination to pursue this kind of independent scholarship. It will take time. And there’s no one size fits all way to do it.”

The announcement elicited a stream of questions but one of them struck particularly hard:

Are you anti-university? Why else would you purposefully do your work outside one?

The question was invited into one of our many conversations and it left us – if we’re being honest with you, dear Scholar – a little bit ... .muted. We found ourselves unable to jump to quick binary answers involving ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Instead, our answers followed with ‘well….’.

We found ourselves appreciative of the question because it provoked us and demanded our attention.

We also began to think of how this was in fact not the first time one of us were asked a question of these sorts relating to our thoughts on the university. A week or so before this question was directed toward The Tatler, both of us were asked the following question during the recording of a podcast episode:

“So, the thing that I've really come across as a challenge in my own scholarship and academic journey is that despite their flaws, universities seem to remain the dominant institutions of learning and knowledge production. Do you see that dominance as something that can be meaningfully challenged or do scholars need to learn how to work alongside and outside of it?”

This was definitely neither a binary nor as pointed a question as the one that The Tatler was individually asked. However, we couldn’t help but now see the overlapping contours between the two questions aimed to unearth how we thought of, saw, related ourselves to the university.

That we were being asked such questions was perhaps not only understandable but also to be expected. We regularly and publicly write about research, knowledge, and scholarship which is often contextualised in the university. Oftentimes, our writings about the modern university may even be said to be acerbic. We don’t hold our tongues when it comes to stating what we find most unsettling and unbecoming of our higher education institutions.

No wonder, those in our scholarly circles want to know what we really think of the university.

Anti-University: Scholarship Before, Within, and Beyond The University

— Written by The Critic and The Tatler

In 1949, when James Killian was inaugurated as the 10th president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he delivered a most interesting speech on the ideals and obligations a private Institution of Technology – like MIT – would be striving to uphold in the second half of the 20th century.

In this speech, Killian defines a private institution of technology as “a special type of educational institution which can be defined as a university polarized around science, engineering, and the arts. We might call it a university limited in its objectives but unlimited in the breadth and the thoroughness with which it pursues these objectives. It includes an undergraduate school and a graduate school as coequal parts of a homogenous faculty... a school of engineering and applied science working in close association with a school of basic science.... enriched by the social and esthetic values of architecture and the humanities...”

Speaking of the primary obligation of such institutes, he set forth that “the education of men and the conduct of research to keep [science’s] frontier endless” would continue to lie at the very core. Further reminding his audience that “one of America’s greatest sources of strength” was “its unequalled industrial capacity”, he stressed the “major responsibility” schools of science and engineering bore toward “educating men for the refinement and management of this productive machine.”

While he recognised the “close relationship to government and industry” that such institutes of technology maintained, he was also of the view that they “have an obligation to keep themselves strong and independent... [as] to curtail freedom in our institutes of technology would be to run counter to the spirit of science, which thrives best in an atmosphere of freedom practiced with responsibility – the responsibility of a company of scholars governing themselves."

For Killian, science and technology were not only “essential to health, prosperity, and security” but also forces that “give you and me more freedom to be socially responsible citizens, to be good neighbors, to pursue the good life, to seek ways of making it unnecessary ever again to divert science away from its normal peaceful objectives…”. In this sense, he held that “a special responsibility lies upon our institutes of technology not to neglect basic science”. This responsibility, as he described it, was “the need to cultivate science for its own special values, its disinterested search for truth, its creativeness, its readiness to acknowledge error and accept new ideas…”

Carrying this line of more romantic – rather than utilitarian – thinking further, he also opined that “education is to be found not only in the classroom or the laboratory, but in the experience of living with one's fellows in an environment stimulating to intellectual activity…”. In this manner, the goal was “to carry further the development of an environment at MIT which performs in the broadest sense an educational function itself” whereby “students need not only meet rigorous requirements” but have “the opportunities to reflect, to develop the intellectual maturity that comes only from self-education.”

A few reflections come to mind when considering these objectives and obligations of private institutions of technology as set forth by Killian in his inaugural speech.

The objectives Killian laid out some 75 years ago for private institutions of technology sound, to us, uncannily similar to the missions most contemporary universities today espouse. While we have not quoted any of Killian’s references to the Atomic Bomb and Cold War above, if we looked past these historically specific moments in his speech, there is little that would seem out of place had it been delivered at a graduation ceremony six months ago. To us, it almost seems like contemporary universities have adopted these objectives that were once considered ‘unique’ to private institutes of technology.

However, when reading the speech against the immediate historical context in which Killian delivered it, we can be sure that there were no motivations at the time for other forms of educational institutions – that is, not private institutions of technology – to take up these ideals and objectives. If anything, while public universities and liberal arts colleges may have shared overlapping roles, Killian ultimately saw them as serving distinct functions within the American education system of the period.

This Essay is a Premium Letter

Become a premium subscriber to read the rest of this Essay and access the full archive. (If you are a member of Scholar Square, our online digital community, you need to explicitly trigger your access. Log in to Scholar Square - instructions on how to get access to The Scholarly Letter are in The Welcome Hall)

Already a paying subscriber? Sign In.

Premium subscribers receive an edition of The Scholarly Letter every Thursday:

- • Two editions of 🍎The Digest every month

- • Two editions of 🍏 The Thursday Essay